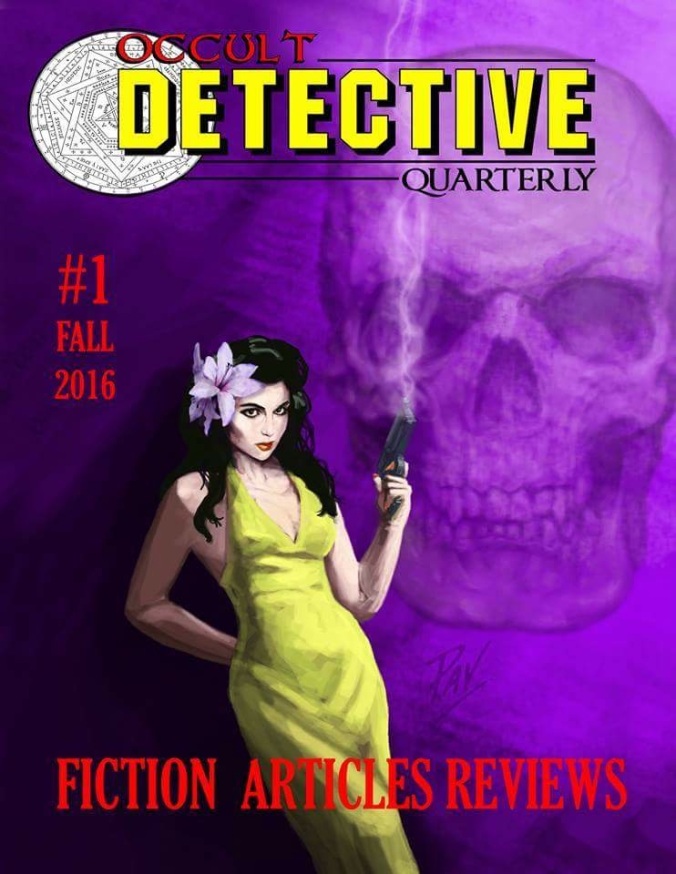

Sometimes you wonder if you have something special on your hands—something that will be, if not famous, then at least a name to conjure with in the right haunts. Occult Detective Quarterly #1, edited by John Linwood Grant and Sam Gafford, is just that sort of magazine.

For my own bottle of champagne smashed against the hull, this review will look at every piece of fiction in some depth, and peel back the layers of this excellent first issue.

My particular favorites were those by David T. Wilbanks and William Meikle, Amanda DeWees, Josh Reynolds, and Aaron Vlek—all of whom turn in outstanding stories.

You can purchase Occult Detective Quarterly #1, right here.

Got My Mojo Working – David T. Wilbanks and William Meikle

Gus is an occult detective.

Gus, in the fine occult detective tradition, could be played by Humphrey Bogart.

Gus, in the fine occult detective tradition (as played by Humphrey Bogart), needs his booze, needs his “cigarettes” (his yellows, here), and needs his wiseacre narration as he encounters a bevvy of dames and weaker men.

Gus, I hasten to add, is a gorilla.

Yes, really.

It’s a lot of fun. That’s the word Wilbanks and Meikle worked for, and they earned it.

As someone who loved Agent of Atlas’ Gorilla Man to no end, this story was perfect.

What hurts the story is the plot’s intense tradition. If you’ve read almost any dozen occult detective stories, you’ve seen this plot a dozen times. I’d imagine the authors did this for something familiar for readers to cling to, given the protagonist, but it’s the one weak point in an otherwise outstanding tale.

The way Gus finally deals with the occult menace is fresh, but it needed some ramifications to sell itself. For something so apparently big, there’s no consequence. Hopefully future stories will play with what happens if you even try to dispose of a demon that way.

When Soft Voices Die – Amanda DeWees

DeWees turns in a “traditional” sort of Gothic.

But where Wilbanks and Meikle’s story stumbled a bit thanks to the traditional trappings, DeWees wisely adds to the proceedings: how the ghosts leads on our protagonist is new, and the cast’s characterization is used to cover any over-familiar spots in the proceedings.

It’s quite a remarkable little story, and one of the highlights of the issue. I won’t spoil it, but I do have one glowing compliment to give:

DeWees knows her history. I don’t have words for how much I appreciate that. She realizes that while Victorian England was rather blasé about unmarried women—even actresses—rooming wherever, and that English attitudes toward sex were rather lax, Victorian east-coast Americans were more intense, insanely prudish than the ahistorical notions about Victorian English sexuality ever imply. Finding an author who’s done her homework, instead of relying on unresearched cliché, is thrilling.

I hadn’t been aware of Amanda DeWees before. Now, I’m impressed; she’s a talented writer, and I need to buy some of her books when I have a chance. She’s someone I would love to publish.

Don’t Say I Didn’t Warn You – Adrian Cole

This is the latest story in the long-running Nick Nightmare series. A fan of the series will probably feel very differently about this story than I did. Me? Mostly, I just have questions…

Was Arabella a recurring character in the series? Is her ending something that I should be emotional over, or is she only in this story? Why can’t the bad guy’s magic be reversed? What, exactly, is Pulpworld? How does magic work in this universe?

As someone who encountered this series for the first time, I’m a bit confused. It’s not a bad story by any means, but having answers for the first three questions provided for new readers would go a long way toward helping my enjoyment.

It’s well written. The characters are well delineated, and interact well. The plot has quite a bit of promise.

I only didn’t have enough details to immerse in this world.

Orbis Tertius – Josh Reynolds

Josh Reynolds is remarkably reliable.

I don’t mean that in the insulting sense it’s so often used, where “reliable” implies “workmanlike” which implies a cuss, or where “reliable” is only another way to say “tired.”

I mean it in a personal sense. I’ve yet to read something of Reynolds’ I dislike. There are stories I, personally, like less, because the elements are less personally appealing to me. But those stories are by no means weaker, and by no means less enjoyed by me.

Remarkably reliable. Reynolds knows how to tell a tale.

“Orbis Tertius” is a story where every element greatly appeals to me. Borges? Adventurers’ clubs? Mind viruses? Some toying with form and format?

It helps that St. Cyprian and Gallowglass are so well developed. They’re among the most meaningfully well-developed occult detectives—which is to say that while we don’t have many hard facts on their lives, their personalities and attitudes are so actively developed that there’s no mistaking them, and no losing them in the crowd. To use the same word again, they’re remarkably like Holmes and Watson in that way. We don’t need hard details to pretend they’re people; St. Cyprian and Gallowglass as alive as our own friends.

There’s no mistaking St. Cyprian and Gallowglass for anyone else in their genre, and Reynolds’ stories are all the richer for it.

MonoChrome – T.E. Grau

I’m going to spend quite a bit of time on constructive criticism for this story. I’ve noticed some other reviews note that this is the story that didn’t work for them, and I’d like to take a peek at why that might be the case—and why this story seems to be the odd man out.

It’s probably worth noting my criticisms don’t come from a place of “I don’t like stories of this sort told in this style”—Grau reminds me quite a bit of Hannah Lackoff, or an early Neil Gaiman, who are two of my favorite authors. With revision, he can begin to reach for their heights.

“Monochrome,” despite some good ideas, has serious issues holding back.

The most immediately apparent issue is striking, but the least of “Monochrome’s” problems: you could cut this story down by more than half, and miss none of its essential beats. It’s a slim story floating in a sea of “extraneous stuff.” We’re starting here because this issue is a symptom of the story’s actual problems.

The pace is glacial, and the glaciers the story chips through are massive. Development of character, plot, or world is slow in coming, and small when it arrives.

I’d like to compare “MonoChrome’s” pacing and development issues to an 18thWall release. This isn’t because I published it, but because A) I’m familiar with its contents and, more importantly, B) its already won awards. When I say this author know what she’s doing, it’s not merely my word backing it up.

M.H. Norris’ The Whole Art of Detection has quite a few scenes that could be considered extraneous. We could easily cut the prologue, and we could easily cut Dr. Baynes’ speech, and we could very easily cut most of her conversations with friends or colleges, and many of her interrogations could be trimmed to the quick. I’m sure, in a mad dash for story-only, you could cut 40-60% of the novel. However, I guarantee you that version would not have placed fourth in the Preditors and Editors Reader’s Poll; I’m sure it wouldn’t even have been nominated, except by a slip of the hand. That space is needed to develop and build the characters, establish the world, and sell the reader’s interest in the story itself.

Character-building, which is another way to say empathy-building, is necessary.

“Monochrome” doesn’t really do this. After reading the story twice I can’t tell you a meaningful thing about the protagonist; and, even, I had to check the story to remind myself of their name. So much of the character work is attempted in the prose rather than established in conversation or action, which leads us to the core problem…

It breaks my heart that what could be good character-building is flatly told to us. He’s afraid of what could happen when the victims’ names are released. He has few joys left in life, but covering chaos. He thinks rich people are the same as gangbangers. All of these things which should be embedded in the character—as we saw with Norris’ novel—and could be meaningful, are flatly (and briefly) listed in the prose before the author goes back to the sea of words. It wouldn’t change the character or our perception of him if they were embedded in the story itself, however; it’s the thin facts of characterization, the “so-and-so likes M&Ms, but hates Twix” sort. Except in this case “so-and-so likes writing about chaos, but hates rich people.”

Grau hasn’t mastered, and doesn’t attempt, the sort of abiding character-development that Reynolds and DeWees excel at. Put any other characters in their stories, and the story fundamentally changes. Put almost any other character into the place of Grau’s protagonist, and the only thing that changes is the surface likes and dislikes. The story runs the same course. His protagonist is surface deep, which hurts a novella-length story.

The best bit of character building—one of the rare spots where the prose, dialogue, and characterization work hand-in-hand to approach that sort of abiding characterization—is when the protagonist reveals what a jerk he is about there being a new out-of-town bartender in “his” bar. It’s a great moment. It’s the one time the protagonist’s instability and nature comes out through the story, and it’s a moment no other protagonist would have captured. The story needed much more of this.

So much of the above would be forgivable if it were written well. I don’t mean “so much of this would be forgivable if it were written with the pose and grace of Edgar Allan Poe on a bender,” but rather, I mean: “so much of this would be forgivable if it were written clearly, cleanly, and with a sense for the reader.”

That last point is important. Grau does not write with the reader in mind. Run-on sentences run rampant. Sentences lack a defining goal, or sometimes even a subject. Many sentences are what should be three or four distinct sentences all strung together, occasionally without even so much as a comma.

The author tries to set a sense of pace, and a quirky character viewpoint. We’re told of cinderblock heads and other unusual images in long, thick streams. But, ultimately, the reader becomes lost in the verbage.

Does it set mood? Setting mood may not tell us anything, and often does not sell character, but it certainly has a place in horror and dark fantasy; it’s vital, and it’s necessary, and it can take up quite a few words.

I suppose some of it sets mood. The second through fourth pages of the story are almost exclusively attempts to set the mood, and inform the reader that LA is a horrifying mess. But there’s something unbalanced in a story when that much time is spent developing a mood, especially though thick paragraphs with run-on sentences and few defining images, without telling us a word about any of the necessary ways to interest a reader. It’s like reading worldbuilding without the world or characters to hang it on, or static mood—and mood needs momentum to set in. At times, it’s more of an essay on LA than a story.

So what are all of these words doing here?

Let’s talk about one of the best, and most heartbreaking, pieces of writing advice I’ve ever received.

Once upon a time, when I was very young and very, very stupid, I spent a week on five thousand words. Every sentence had to be mood and poetry and something NEW. Every sentence had to be perfect. Five thousand words of it. Heaven help me. They read it—all of it—out loud. Heaven help them. The reader turned to me, and said, “That’s a bit much dark chocolate. It’s too rich. We need cake bits to get it down.”

Young, innocent James was crushed. Old, cane-waving James thinks it’s probably the best bit of advice he got at that point in his career.

While I would say “dark chocolate” is an overestimation for both my and Grau’s stories (we are neither Ray Bradbury), I think the comparison is clear.

Occasionally Grau hits on a gorgeous line—“he liked this time of day, when the sun gave up…”—but the dark chocolate effect sets in, burying the flash of light under comparisons of buildings to pimps, a lake called “the broken promise of the eighteenth century,” a meditation on how the diamond-shine of old Hollywood gave way to pale, eyes that were every color except purple or red, or any of several dozen other attempted confections in the space of about three or four hundred words.

I actually pulled that from a single, particularly story-rich page, where we meet presumed cultists and learn about the victims. A several hundred word stretch, with that much storytelling ground to cover, and we’re still trapped in a dark chocolate bakery without learning anything meaningful about the characters, the world, or even the story itself. We learn nothing about how the protagonist reacts to either of these things; and only a little bit about how the world twines with these elements. The paragraphs with story are almost entirely separate from the paragraphs with mood. All of which means that we essentially just have two blocks of story, untempered by character or world or mood, sitting in the sea of attempted mood. All of which gives the story the feel of jerking back and forth on the gear-shift, as spin from examining Story to Mood and back again.

The author is trying harder to write well than to tell a story well, or develop a character well, or develop the world well. “MonoChrome” suffers as a result.

The author isn’t a poor writer. He could write excellent stories.

He only needs to learn that characters and story come first, the joys of dark chocolate writing second—and in their own way. Grau shows promise.

Baron of Bourbon Street – Aaron Vlek

Aaron Vlek is another writer who is entirely new to me. “Baron of Bourbon Street,” however, is the kind of story that convinces you to quickly check for an author’s other work. The case is creative, the characters are well-drawn and fresh, and the writing stands at a consistently high level. The creativity never ends.

Vlek’s use of Baron Samedi is perfect, and it’s great to see someone not only turn in a “voodoo” story, but turn in one that’s done its homework and turns everything to its own effective. I could write a few dozen words on the brilliance of making the Baron one half of an occult detective team, but that would be telling.

Vlek is another author I’d love to publish. She knows what she’s doing.

The Adventure of the Black Dog – Oscar Dowson

There’s no meaningful character development, there’s no tension (and, in the end, we discover there was no need for anyone to even begin to feel tense), and there’s no development of the world or magic system. The Holmesian references felt unnecessary: the story doesn’t gain anything with an Edwardian, ersatz Watson and magician Holmes, it’s simply a curious addition to the writing that’s unearned and gets in the way of Dowson’s magical recruitment story.

This is my biggest problem. Dowson writes well, the haunt is unique, and what light touches of characterization bubble up are handled well. But at no point is there, properly, a story with a beginning, middle, and end—it’s as though we’ve just read the establishing prologue of a novel, with elements set up, and then we’re left this prologue as though it stands alone. It’s not only as though we’ve read the first chapter of A Study in Scarlet as if it were a standalone, it’s as though we’ve read it and felt Holmes’ presence was entirely unnecessary.

I’d like to see more of Dowson’s writing, however. He shows promise as an author.

Occult Legion: “The Nest” – William Meikle

William Meikle is a master of three things:

1) Storytelling,

2) Occult detection,

3) Weaving his stories into a single, cohesive world.

The first chapter of this occult detective round robin novel won’t do anything to change that perception. I look forward to seeing how future authors continue the tale.

Sundry

Tim Prasil’s “How to be a Fictional Victorian Ghost Hunter (In Five Easy Steps)” is a charming piece about the occult detective forbears, and the oddities of their tropes. It’s the standout article.

Charles R. Rutledge’s Doctor Spektor double-header (an overview of the comic series, and an interview with the original author) is fine enough. My tepid review has less to do with Rutledge’s work, and more to my indifference to summarizing “This thing I enjoy exists, and I will now talk about it” articles. As an argumentative person, I prefer arguments made and points fought for. If you enjoy this sort of article, you’ll find points to recommend it.

Lastly there are reviews by Dave Brzeski and yours truly, which, I flatter us to say, are uniformly excellent.